THE FABRIC OF PHOTOGRAPHY (2021)

My mother, Violet, Rhyl, 1955, photograph by my father, Brian Edwards

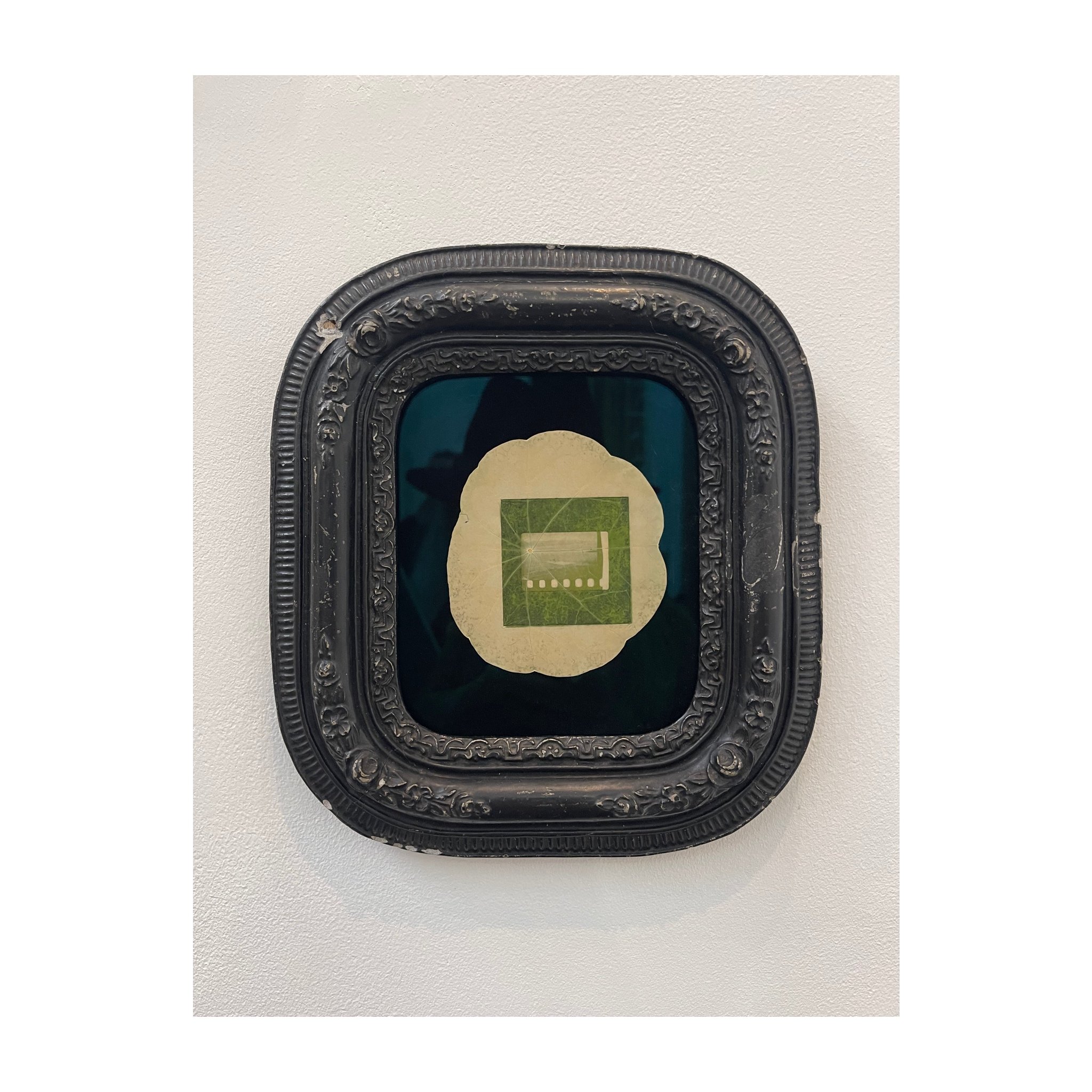

A selection of my Anthotype and Chlorophyll print works were shown in Fabric of Photography, a 2021 Photo Oxford Festival event at the Old Fire Station Oxford. The exhibition featured work by an international group of twelve contemporary artists working with historical analogue processes and asking questions about photographic materiality. I wrote the following essay for the catalogue.

The Colour of Memory, The Memory of Colour

My mother isn’t speaking to me. This time it’s about a photograph. Mum believes that I took it without asking. She wants it back, a black and white shot depicting her as a pretty young woman standing in front of a seaside photo booth. Admiring Mum’s vintage outfit and wanting to take a closer look at the pattern of her cardigan, I place my thumb and finger on it, then spread them apart. The image remains static, reminding me that I’m holding a piece of paper, not looking at a screen.

A photograph may be your most treasured possession, but a photograph is latent, passive, incapable of igniting family feuds, unless invested with such power by our imaginings and emotional interventions. In the seeking and discovering of ourselves within the tones and contrasts of a photographic print, we become as one with a chemically coated piece of paper, believing it to define our identity, our history, our culture. Furthermore, that it preserves the memory of a moment. The paper reliquary that holds a fragment of my mother’s youth is fragile, so I ask her: will a copy do? No, she is adamant, she wants the original, thank you.

My parents met as children whilst attending a school for the visually impaired, where my father trained to be a professional photographer. As an experienced darkroom technician, he is able to identify the paper a photograph is printed on by examining its tonal range, or by touch and, sometimes, by smell. He tells me that he always printed weddings on fine white lustre paper: “this gave an artistic appearance to a practical photograph.” His favourite for portraits was Agfa Portriga Rapid because “it produced a warm, almost sepia image, but still kept its black and white qualities” He feels certain that it would upset him emotionally to see a photographic portrait printed on glossy paper.

Laying aside artistic and technical considerations concerning materials that determine the qualities of a photographic print, the experience of growing up with partially sighted people instilled in me an awareness that beyond the visual, a photograph has other sensory dimensions. It doesn’t matter to my mother that, at 82 years old, she is now totally blind and cannot see the image of herself as a young woman, she wants to feel the object, run her fingers over its satin coated surface and along time-worn edges, sniff the itchy, still-lingering odour of sulphur dioxide gas. Holding it in her hands, she’ll feel seventeen again, in love with a boy whose clothes smell of photographic chemicals.

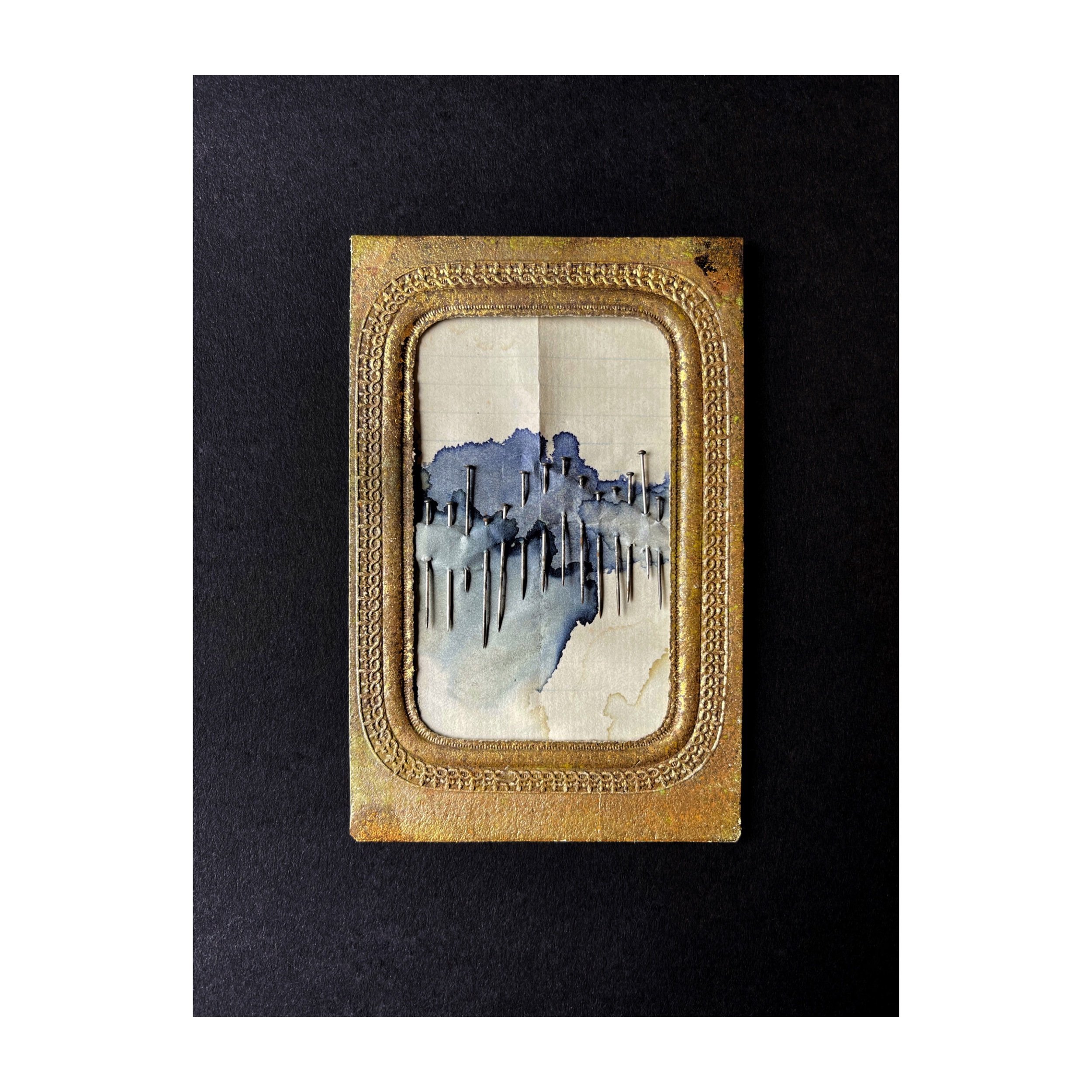

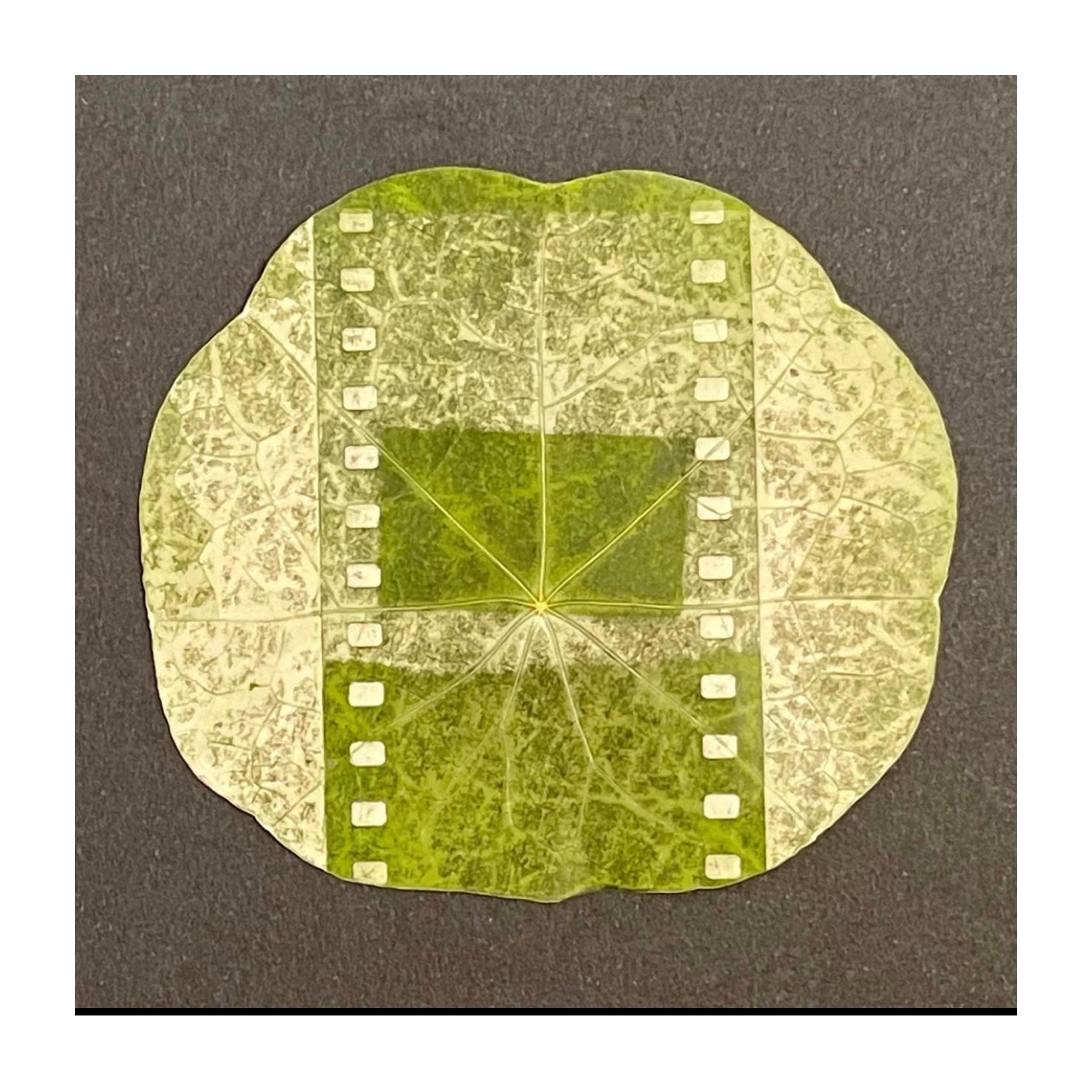

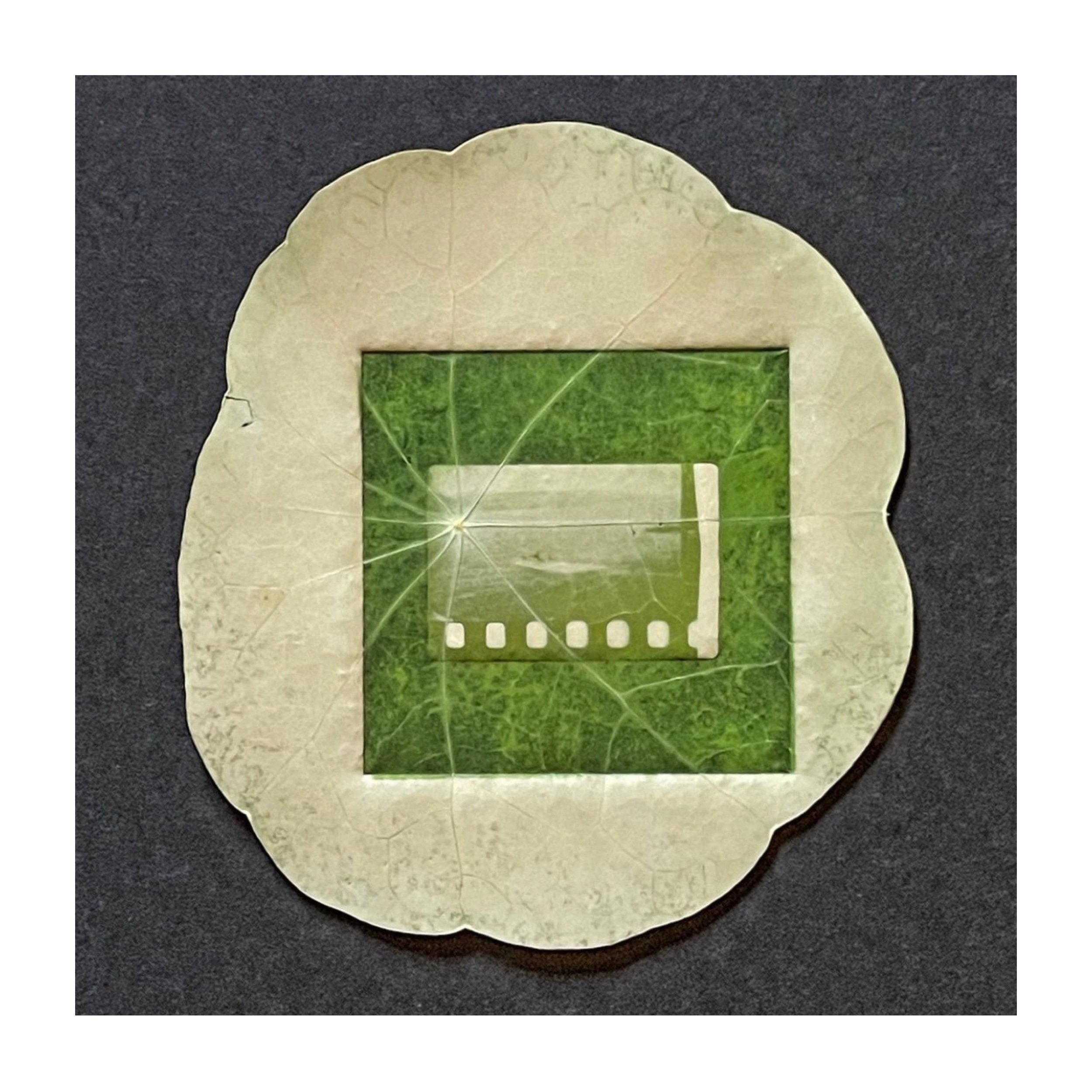

My father worked with toxic, noxious substances, recalling that “Ferrania colour slides were the first ones you could develop at home. “Your mother used to go spare, it stank the kitchen out!” In my own photographic practice, I have chosen to utilise safer, sustainable, plant-based processes, most notably, Anthotype and Chlorophyll printing. Each piece of work begins with a seed and may take many months to produce. If stored in a dark, dry place, papers coated with plant emulsion will retain their colour fastness for years. Yet once they have been exposed to sunlight, even if returned to the dark, Anthotypes will continue to soften and fade until they vanish completely. Thus they are time based artworks, ecofacts whose materiality embodies movement. Working within a cycle of cultivation, making, and letting go, engages me with the creative and philosophical implications of material impermanence, the passage of time, failing vision, losing and forgetting, and the inevitability of death.

What is left of a photograph when it can no longer be seen or its subject matter remembered? Triggered by her heightened sense of touch, light captured over sixty years ago continues to illuminate my blind mother’s memories. My partially sighted father swears that he can smell the difference between Bromide and Bromesko papers. I have observed that the aroma of plant emulsion may be detected long after an Anthotype’s pigment-captured image has faded. Vestiges of sticky, sweet spearmint; piercing, medicinal Rosemary; pungent, intoxicating sage: ghosts of light and life, still breathing memory within the materiality of paper substrates: the colour of memory, the memory of colour.

Nettie Edwards 2021